NOTES:

In this printing of the thesis, there are no images. Allimages for the thesis will be provided with ‘long descriptions’ foraccessibility reasons and these will be incorporated into the text.

The appendices are also not included.

The images and appendices are all available online in themaster version of the thesis at

TO DO:

Table of contents, figures and tables (complete labels etc)

Glossary (definitions of terms from thesis)

Summary of thesis (1000 words)

Timeline of author’s contributions

AccessForAll: Metadata forUser-centred, Inclusive Access to Digital Resources

ElizabethAylward Nevile

BJuris/LLB (Monash) MEd (RMIT)

School of Mathematical and GeospatialSciences,

Science, Engineering and Technology Portfolio, RMIT University.

month and year when the thesis is submittedfor the degree.

Except where due acknowledgement has beenmade, the work is that of the candidate alone. The work has not been submittedpreviously, in whole or in part, to qualify for any other academic award. Thecontent of the thesis is the result of work that has been carried out since theofficial commencement date of the approved research program. No editorial workhas been carried out by a third party and ethics procedures and guidelines havebeen followed.

for ref guides see

Acknowledgements

This research has had special assistance from a number ofsources. In combination, they have made it possible for work to be undertakenin an integrated and supportive environment. The early analysis of accessibleWeb Content Development (Appendix 8) was supported financially by a number ofAustralian and international agencies. The research has been supported duringtwo periods at University of Tsukuba in Japan where the author was a verygrateful Visiting Research Scientist.

Some documents based on the research were co-authored incollaboration with members of the IMS Global Learning Consortium, the DublinCore DC Accessibility Working Group, ISO/IEC JTC1 SC36, and members of theINCITS V2 Working Group and MMI-DC Accessibility and Multilingual Workshops(see Appendices 1 and 2). The author was a working member of all these workinggroups and is grateful for the environment they created.

| Supportive bodies | Description of assistance |

| IMS Australia, participating in the IMS Web Content Accessibility work was supported by DEST. | |

| IMS Global Learning Consortium Accessibility Working Group - in particular, Jutta Treviranus, Madeleine Rothberg, Cathleen Barstow, Andy Heath, Hazel Kennedy Anastasia Cheetham, David Weinkauf, Mark Norton, Alex Jackl and Martyn Cooper. | |

| http://www.linguistics.unimelb.edu.au/ | Paul Gruba |

| MELB-WAG | |

| Martin Ford, Martin Ford Consultancy, with whom the author undertook accessibility and metadata standards work in Europe. | |

| University of Melbourne, Department of Information Systems, for a grant to work on WebCT's accessibility, accommodation and a friendly environment in which to work. All were essential and appreciated. | |

| Oregon State University... | Particular thanks to John Gardner and others for their help with the difficult topics of haptic representations, mathematics, science etc. |

| | Very special thanks to Charles McCathieNevile for his encouragement, sharp critique, friendship and, of course, his expert advice. |

| La Trobe University, Department of Computing and Mathematical Sciences, for a position as an Adjunct Associate Professor and making it easy to do research. | |

| University of Tsukuba for wonderful times to work and learn about the Japanese way of life and an interest in further research to do with distributed resources. | |

| | Behzad Kateli, Sophie Lissonnet, James Munro and Sarah Pulis, former students who have been very helpful throughout the research and offered useful technical advice and personal support. |

| and | my very wonderful, tolerant and supportive family. |

Table 1 - Table of acknowledgements

Table of Contents

AccessForAll:Metadata for User-centred, Inclusive Access to Digital Resources

Acknowledgements

Table of Contents

Images and Tables– incomplete???............................................................................... 8

Table of tables

Thesis Summary (1000words - still drafty)................................................................ 11

Abbreviations and Websites................................................................................... 12

Glossary of terms17

Relevant AccessibilityOrganisations.................................................................... 19

Relevant AccessibilityStandards Organisations................................................... 21

Chapter 1: Preamble24

Introduction24

Background25

An outdated view ofaccessibility and the Web....................................................... 30

A new approach toaccessibility for an updated Web............................................... 31

Understanding andsignificance of accessibility..................................................... 33

AccessForAll philosophy35

A metadata approach36

AccessForAll metadatadevelopment..................................................................... 37

AccessForAll metadataresearch........................................................................... 38

Research objectives39

Summary40

Chapter 2: Introduction42

Preliminary, practicaldefinitions......................................................................... 43

Research scopelimitations..................................................................................... 51

Research methodology52

Research activities58

Chapter Summaries62

Chapter 3:Accessibility and Disability...................................................... 64

Introduction64

Understandingaccessibility................................................................................... 64

Models of disability66

Inaccessibility andusers......................................................................................... 68

Disability asfunctional requirements.................................................................... 70

Accessible resources76

Quantifying theaccessibility context.................................................................... 80

Chapter 4: Universaldesign............................................................................ 87

Introduction87

The early-history ofaccessibility.......................................................................... 87

Separation of Structureand Presentation............................................................. 92

The WAI Requirements94

WAI Compliance andConformance......................................................................... 95

Special resources forpeople with disabilities.......................................................... 96

Universal design97

Universal Accessibility- the W3C Approach.......................................................... 98

The UK DisabilitiesRights Commission Report....................................................... 98

Chapter summary108

Chapter 5: Other routesto Accessibility............................................. 110

Introduction110

Beyond 'universal'accessibility......................................................................... 110

Accessible code andaccessible services............................................................... 111

Responsible foraccessibility............................................................................... 112

EuroAccessibility116

A Practical Approach119

Relevantpost-production services and libraries................................................. 120

Chapter summary120

Chapter 6: Metadata122

Introduction122

Definitions of metadata122

Formal Definition of DCMetadata..................................................................... 127

Graphical (andinteractive) metadata................................................................ 133

Chapter summary140

Chapter 7:Accessibility Metadata........................................................... 141

Introduction141

Existing accessibilitymetadata.......................................................................... 141

Dynamic ContentAdaptation Services................................................................ 146

Dublin Coreaccessibility metadata.................................................................... 147

Accessibility metadataand WCAG 2.0................................................................. 149

Chapter summary150

Chapter 8: User needsand preferences................................................... 151

Introduction151

Individual differences151

RelationshipDescriptions.................................................................................... 154

Profiles of user needsand preferences................................................................. 158

User needs as aresource...................................................................................... 161

AccessibilityVocabularies.................................................................................. 161

Chapter summary162

Chapter 9: ResourceProfiles...................................................................... 163

Primary and equivalentalternative resources (or components)......................... 164

The AccessForAllmetadata specifications.......................................................... 166

Facilitating discoveryof alternatives............................................................... 169

User Interfaces171

A universal remotecontrol................................................................................ 171

The URC specifications172

FLUID173

Chapter summary174

Chapter 10: Match andinteroperate........................................................ 175

Introduction175

Matching175

The value of metadata177

Functional Requirementsfor Bibliographic Records.......................................... 182

Interoperability185

Background185

Chapter summary193

Chapter 11:Implementation......................................................................... 194

Introduction194

Implementation194

heading??196

Proof of concept196

Implementationactivities................................................................................... 197

Distributed Accessibility200

The future202

Chapter summary202

NOTEs202

Chapter 12: Conclusion204

Introduction204

Final discussion205

Future work206

References207

Citations - odd?233

Images and Tables –incomplete???

Figure???: Map of Signatures and Ratifications of UN Convention A/RES/61/106 as of 10December 2007 [UN Enable]25

Figure ???:...36

Figure ???: ...37

Figure ???: ...37

Figure ???: Australian Prime Minister's Website (42

Figure ??? The metadataas viewed in a Safari browser (Pandora,2007).__________________ 43

Figure ??? The metadataas viewed in a Safari browser (Pandora,2007).__________________ 43

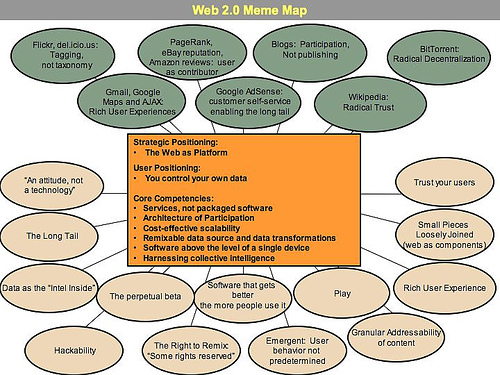

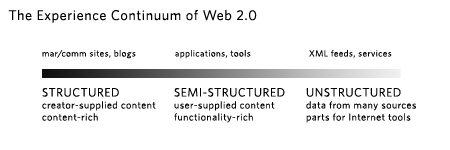

Figure ???: Diagram ofWeb 2.0 (O'Reilly, 2005)44

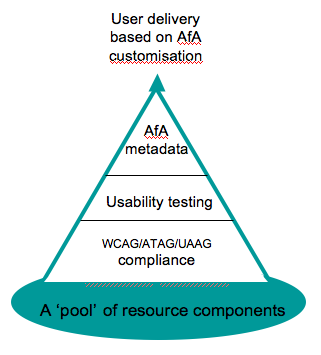

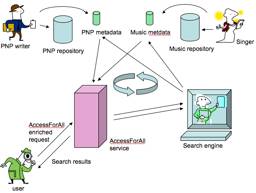

Figure ???: The simpleAccessForAll model that provides individual users with resources that matchtheir accessibility needs and preferences. why this??? explain it49

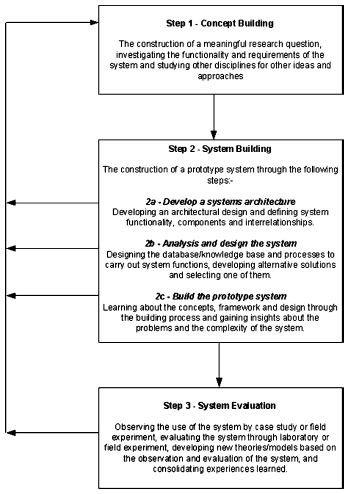

Figure ??? Burstein,System development (Burstein, 2002, p. 153)_________________________ 56

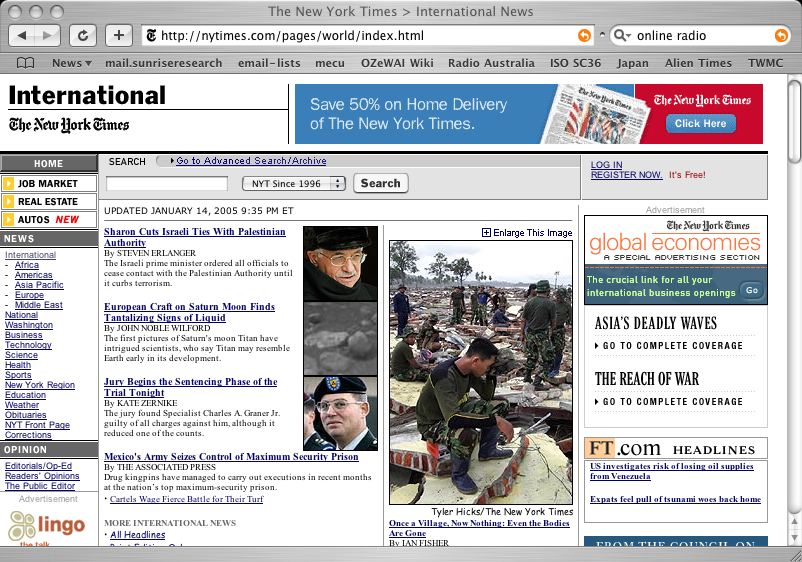

Figure ???: New YorkTimes Online (2005)75

Figure ???: accessibilitypages http://www.humanfactors.com/downloads/markup.aspaccessed 15/1/2005 75

Figure 76

Figure ???: UK GovernmentAccounting Web Page_____________________________________ 76

Figure ???: Demo of twopages - sight vs sound differences (HFI-chocolate,2005).___________ 77

Figure 79

Figure 80

Figure ???: Likelihood ofdifficulties by population (Microsoft, 2003b)80

Figure ???: Difficultiesby severity (Microsoft, 2003c)81

Figure 81

Figure 81

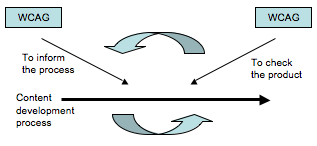

Figure ???: WCAG97

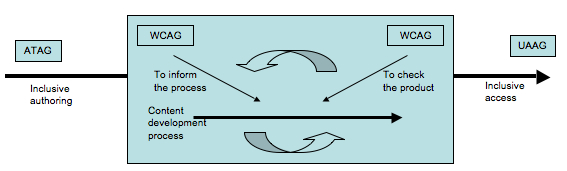

Figure 12: ATAG-WCAG-UUAG97

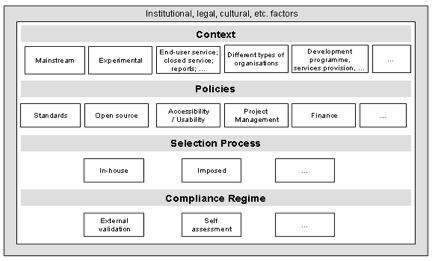

Figure ???: The widercontext for accessibility (Kellyet al, 2005, p. 8)___________________ 107

Figure ???: a tangram (111

Figure ???: A progressiveset of images showing how (RDF or other) tagging of content can be used toseparate content from tags and then the tags themselves can be tagged, orsorted in multiple ways.______________________ 122

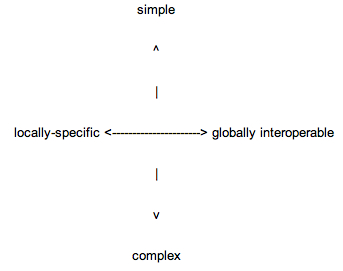

Figure ???:simple/complex; global/local___________________________________________ 125

Figure ???: DC metadataas grammar (1) (Baker, 2000)128

Figure ???: DC metadataas grammar (2) (Baker, 2000)128

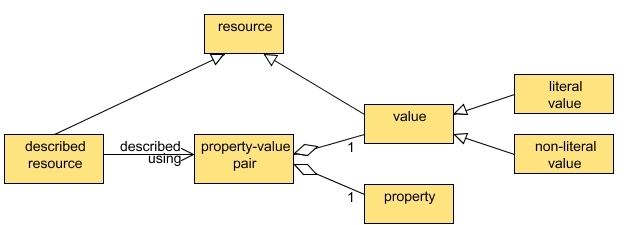

Figure ???: DCMI ResourceModel (Powell et al, 2007)130

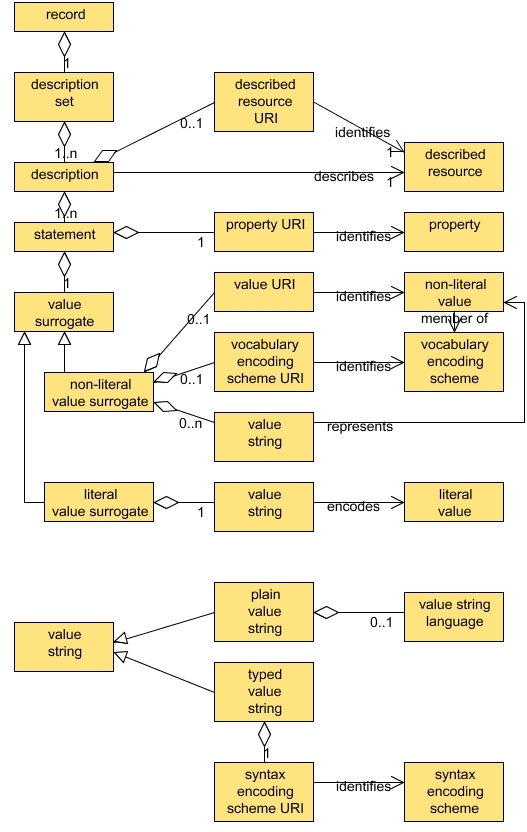

Figure ???: DCMIDescription Set Model (Powell et al, 2007)130

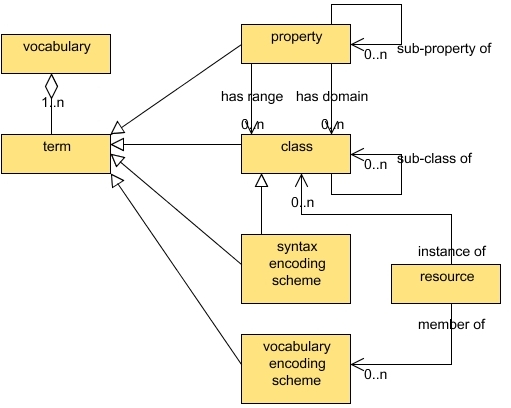

Figure ???: DCMIVocabulary Model (Powell et al, 2007)130

Figure ???: The SingaporeFramework (Nilsson, 2007)131

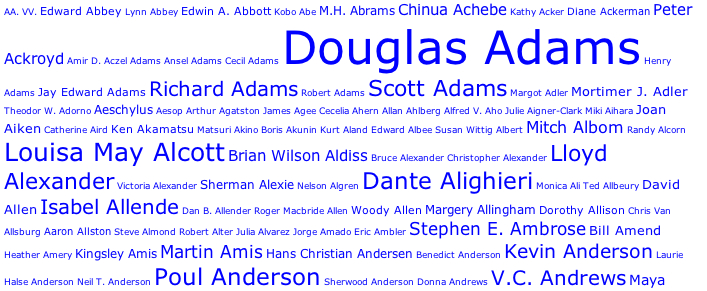

Figure ???: A tag cloud (134

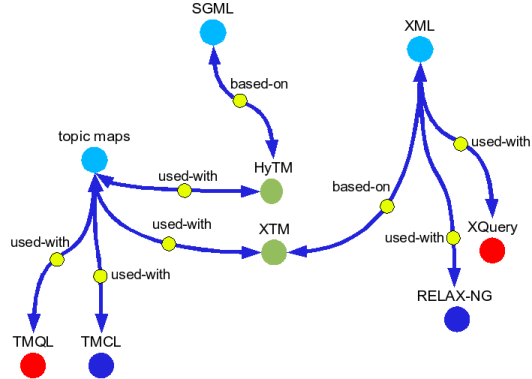

Figure ???: Topic maps???_____________________________________________________ 135

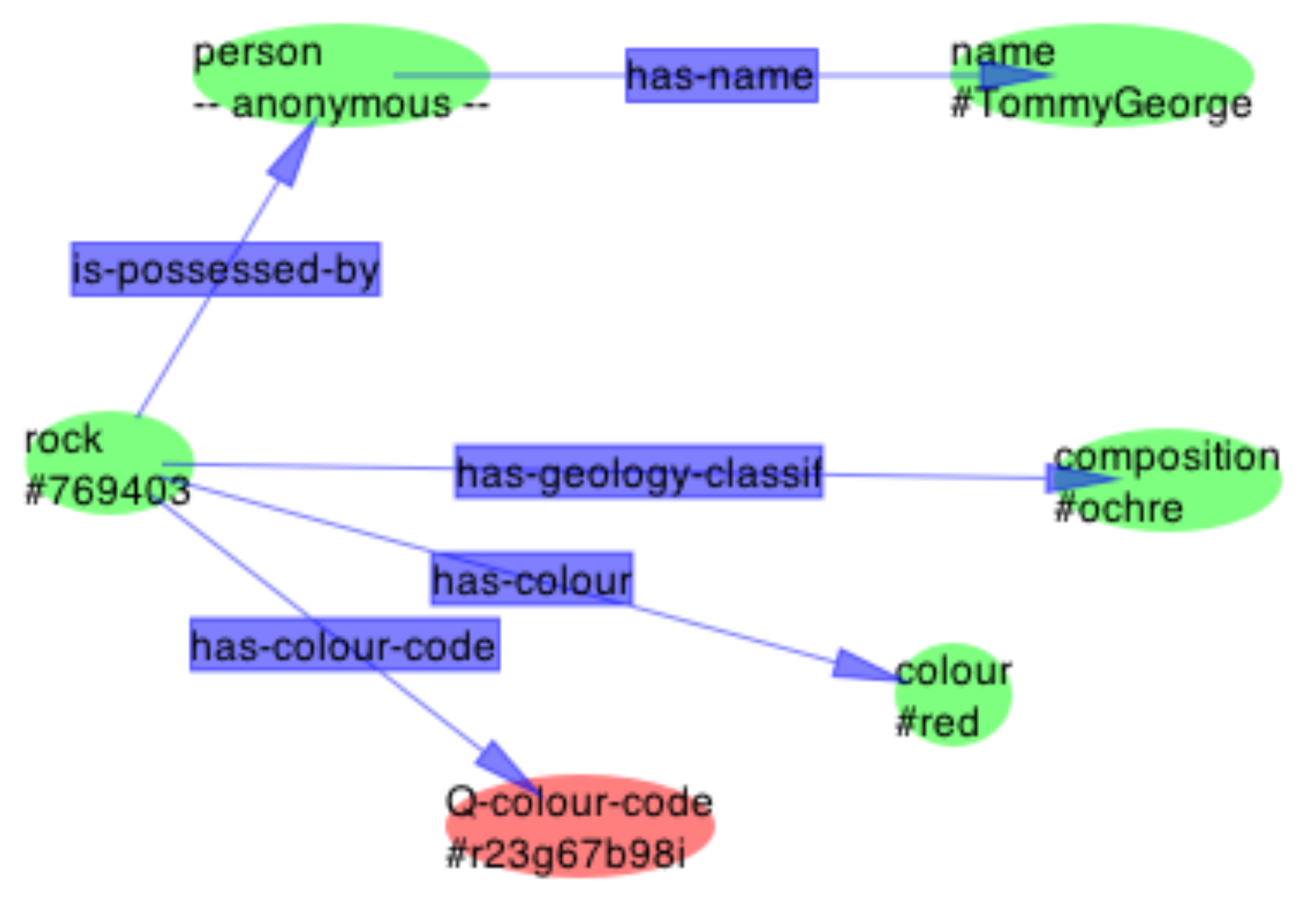

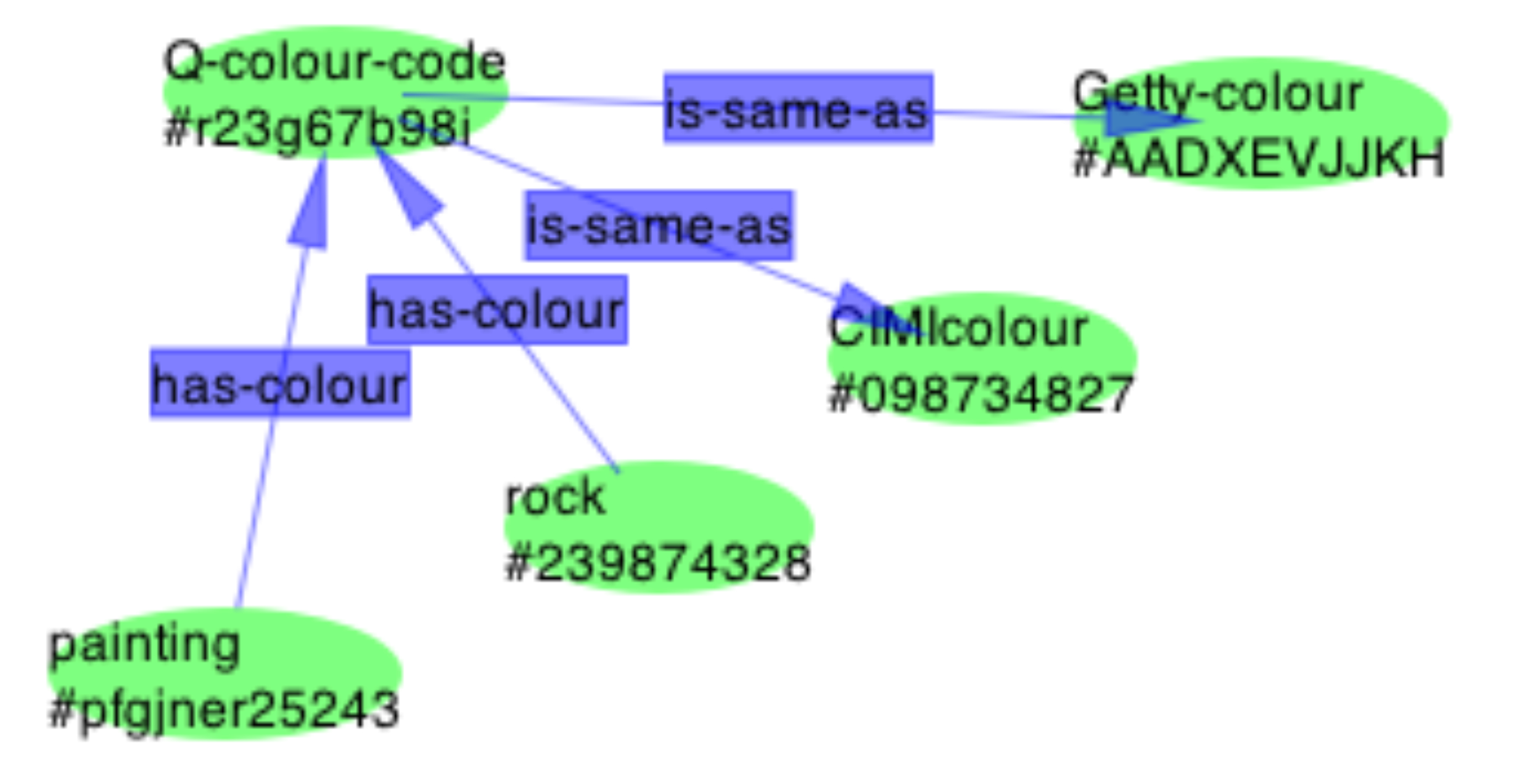

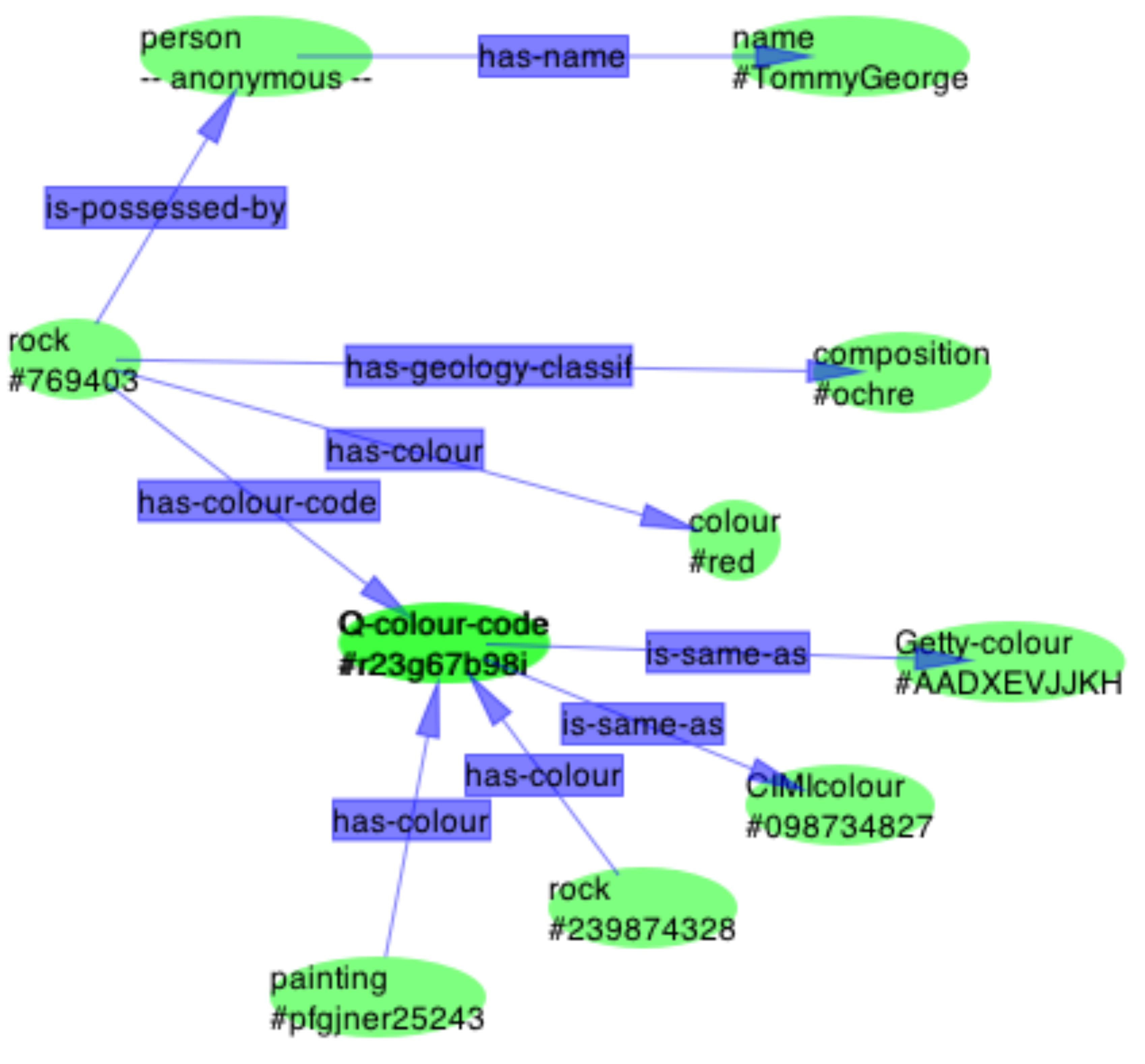

Figure ???: Topics mapsas an ontology framework__________________________________ 137

and138

Figure ???: Front page ofthe Age newspaper on 9/11/2007 in Safari and Opera Mini showing headlines sophone users can easily select what to read or look at.____________________________________________________ 147

Figure ???: AccessibilityAbstract model (Pulis, 2008)148

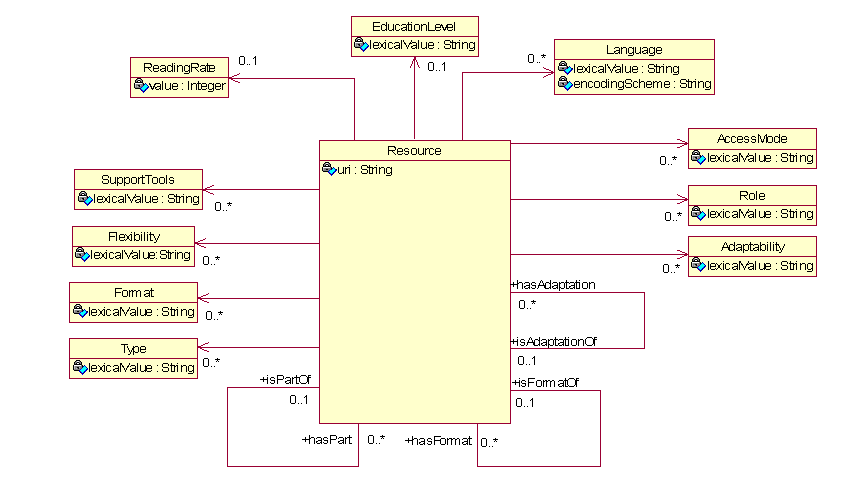

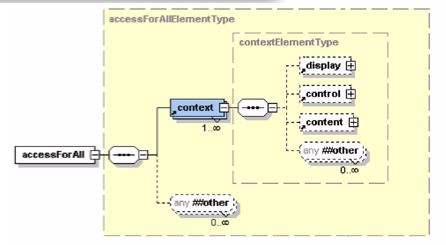

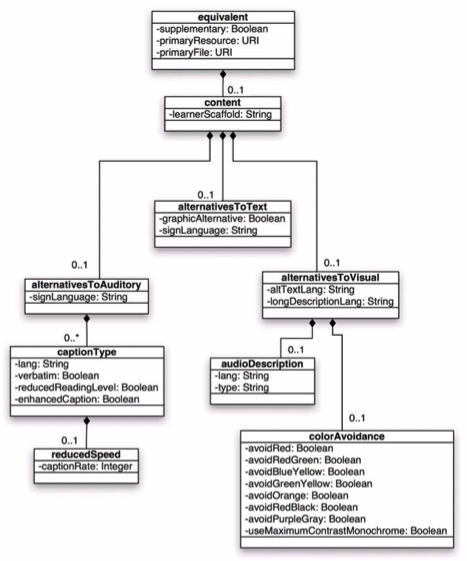

Figure ???: AccessForAllstructure and vocabulary (image from AccessForAll Specifications, [154

Figure ???: AccessExtensibility Statement (Jackl, 2003).157

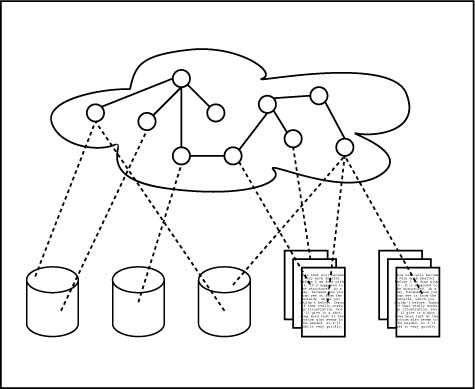

Figure ???: Diagramshowing cycle of searches and role of AccessForAll server158

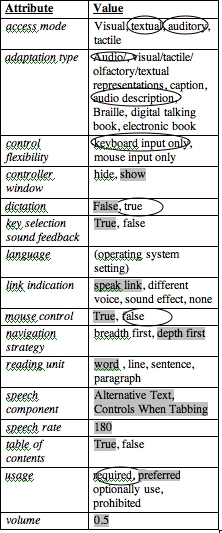

Figure ???: A typical setof user needs and preferences showing the default and the user's individualchoices. 159

Figure ???: What do weneed to know about an object for accessibility?__________________ 162

Figure ???: Multipleinstantiations of a single Web page (HFI-testing).163

Figure ???: IMS structurefor accessibility metadata from 2.3, Page 7, AccMD Norton, 2004_ 166

Figure ???: A user with a voice-controlled URC and a seated useremploying a touch-controlled URC (GottfriedZimmermann).____________________________________________________________________________ 171

Figure ???: A wheel-chairuser struggling to reach an ATM (HREOC (withpermission).____ 172

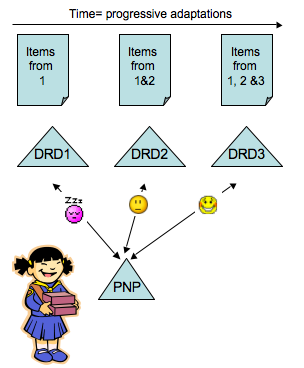

Figure ???: As the itemsare adjusted for matching to the user's PNP, their DRD more closely matches thePNP. 174

Figure ??? A pyramidbased on the Howel model of accessibility ????___________________ 176

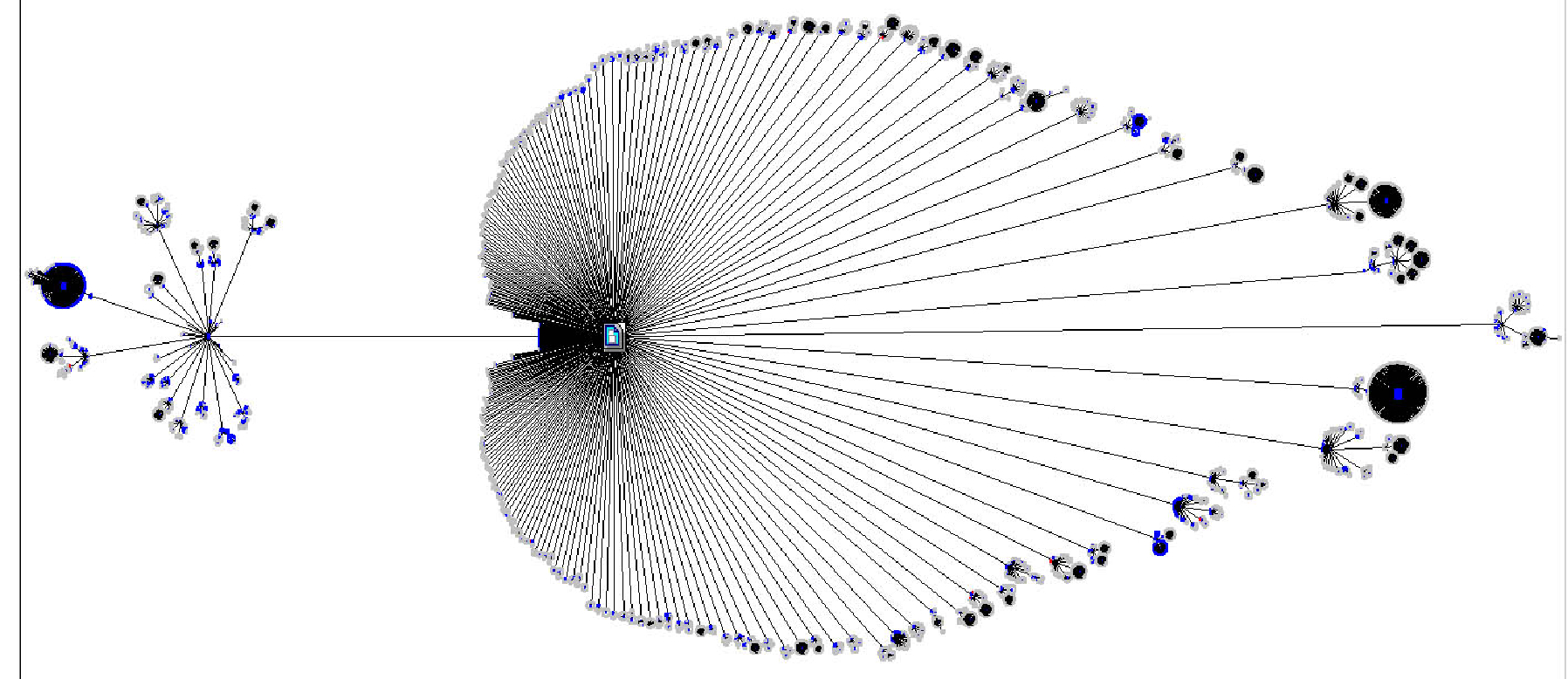

Figure ???: The reuse ofcomponents in the 48,084 pages on the tested section of the La Trobe Web site.from La Trobe Website audit (Nevile, 2004)177

Figure ???: Thebehaviours for interoperability using AccLIP and AccMD in TILE (178

Figure ???: AnAccessForAll process diagram_______________________________________ 180

Figure ???: The modifiedsection of the original diagram with a separate filtering service shownhighlighted. 180

Figure ???: 4 FRBRentities associated with two resources and their possible relationships(Morozumi et al, 2006). 182

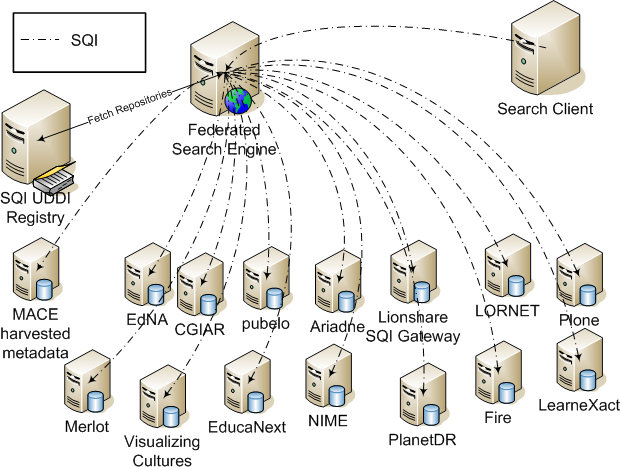

Figure ???: The Globefederated search model using ProLearn Query Language. (Ternier et al, 2008)190

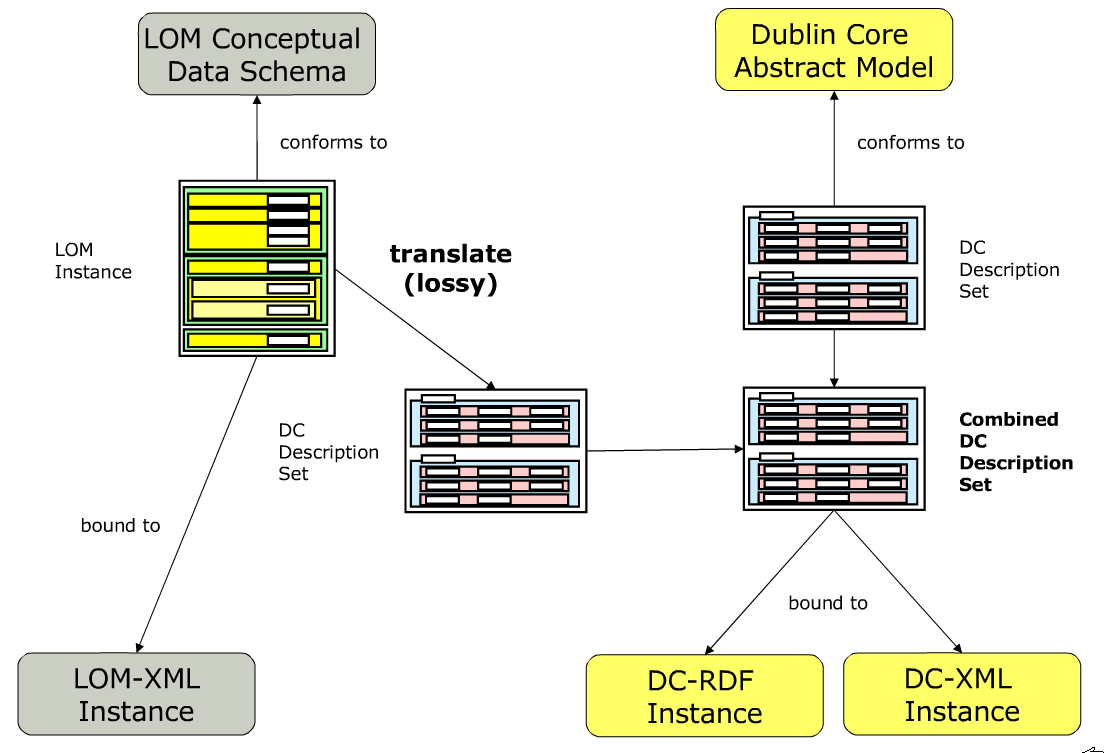

Figure ???: The point ofloss of information in the LOM -> DC translation process (Johnston et al,2007) 191

Figure ???: A possiblestructure of a future metadata standardization framework. from Mikael Nilsson,

Figure ???195

Figure ???: ABC Video ondemand________________________________________________ 196

Figure ???: Thesisstructure_____________________________________________________ 205

Table of tables

| Chapter | Tables |

| title |

table of acknowledgements table of contents table of images and tables |

| post-production | the plan to make WCAG testable |

| acc-metadata | table of services |

| user profiles | AccessForAll structure and vocabulary 6.2.1 Display Preference Set 6.2.2 Screen reader Preference Set 6.2.9 Screen Enhancement Generic Preference Set A typical set of user needs and preferences showing the default and the user's individual choices. |

| resource profiles | IMS structure for accessibility metadata

|

| matching | The behaviours for interoperability using ACCLIP and ACCMD in TILE.

|

| Table ???: Tables | |

ThesisSummary (1000 words - still drafty)

The first decade of internationaleffort to make the Web accessible has not achieved its goal and a differentapproach is needed. In order to be more inclusive, the Web needs publishedresources to be described to enable their tailoring to the needs and preferencesof individual users, and resources need to be continuously improvable accordingto a wide range of needs and preferences, and thus there is a need formanagement of resources that can be achieved with metadata. The specificationof metadata to achieve such a goal is complex given the requirements,themselves not previously determined.

Accessibility is a term often used todescribe property rights and or other aspects of availability of such resourcesor services. In this thesis, the term is used to mean the capability ofindividuals to access digital resources in perceptual modes that areappropriate for them at the time.

Ensuring accessibility of the Web has beena major concern of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) for a decade: thoseresponsible for inventing the Web recognised early that the features such asthe graphical user interface that attracted so many to the Web wassimultaneously alienating many from it, because they could not perceive contentin the form in which most of it is provided. For nearly a decade, the Web hasacted as a publishing medium, and efforts to make the publications accessiblehave been based on a set of guidelines developed by international committees ofexperts led by the W3C. The guidelines have acted as specifications fordevelopers.

More recently, the Web has become less ofa one-way publications medium and, now known as Web 2.0, it is an interactivespace in which resources become ‘live’ objects capable of reformation andreforming other resources.

What this thesis offers is an argument infavour of an on-going process approach to accessibility of resources thatsupports continuous improvement of any given resource, not necessarily by theauthor of the resource, and not necessarily by design or with knowledge of theoriginal resource, by contributors who may be distributed globally. It arguesthat the current dependence on production guidelines and post-productionevaluation of resources as either universally accessible or otherwise, does notadequately provide for either the accessibility necessary for individuals orthe continuous or evolutionary approach possible within what is defined as aWeb 2.0 environment. It argues that a distributed, social-networking view ofthe Web as interactive, combined with a social model of disability, given themanagement tools of machine-readable, interoperable AccessForAll metadata, asdeveloped, can support continuous improvement of the accessibility of the Webwith less effort on the part of individual developers and better results forindividual users.

This thesis argues that metadata isessential and integral to any shift to an on-going process approach toaccessibility. It is at the core of the research in as much as it providesessential infrastructure for a new approach to accessibility. (500 words)

Abbreviations and Web sites

Flickr,

ABCVideo On Demand http://www.abc.net.au/vod/news/

AbilityNethttp://www.abilitynet.co.uk/content/news.htm

AccLIPBPG, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP Best Practice Guide-

AccLIPBinding, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP XML Binding -

AccLIPIM, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP Information Model -

AccLIPConf, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP ConformanceSpecification -

AccLIPUC, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP Use Cases -

AccMDOverview, IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Overview

AccMDIM, IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Information Model

AccMDBinding, IMS AccessForAll Meta-data XML Binding

AccMDBPG, IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Best Practice Guide

AGLS,AGLS Metadata Standard, Standards Australia 5044

AJAX,Asynchronous JavaScript and XML http://www.ajax.org/

Alt-i-lab2005 http://www.imsglobal.org/altilab

APH,American Printing House for the Blind http://www.aph.org/louis.htm

APLR,CEN APLR, http://www.cen-aplr.org

ATAG,Jutta Treviranus, J., McCathieNevile, C., Jacobs, I., & Richards, J.,(Eds), (2000). Authoring Tool Accessibility Guidelines 1.0

ATAGWG http://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-AUTOOLS/

ATRC,Adaptive Technology Resource Center http://atrc.utoronto.ca/

AVCCThe Australian Vice-Chancellors' Committee http://www.avcc.edu.au/

Babelfishhttp://www.babelfish.org/

BrowseAloudhttp://www.browsealoud.com/

CanCorehttp://www.cancore.ca/

CC/PP,World Wide Web Consortium's Composite Capabilities and Personal Preferencesspecifications http://www.w3.org/Mobile/CCPP/

CEN/ISSSLearning Technologies Workshop

CNIB,Canadian National Institute for the Blind

Cornelluniversity Library

CSS,Cascading Style Sheets http://www.w3.org/TR/REC-CSS2/

CWISInternet Scout http://scout.wisc.edu/Projects/CWIS/

DCMI,Dublin Core Metadata Initiative http://dublincore.org/

DCMIAccess, Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Accessibility Working Group

DCMITerms, Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Terms

DCMIDCAM, Dublin Core Abstract Model,

DDS,Dewey Decimal Classification System, http://www.oclc.org/dewey/

del.icio.ushttp://del.icio.us/

digghttp://digg.com

DRC,Disability Rights Commission (UK) http://www.drc-gb.org/

DRD,ISO standard for Digital Resource Description (FCD 24751-3, IndividualizedAdaptability and Accessibility in E-learning, Education and Training Part 3:Access For All Digital Resource Description online at

EARLhttp://www.w3.org/TR/EARL10-Schema/

EdNA,Educational Network of Australia http://www.edna.edu.au/

EduSpecshttp://eduspecs.ic.gc.ca/

FLICKRhttp://www.flickr.com/

FluidDrag-and-Drop

FRBRFunctional Requirements for Bibliographic Records Final Report.

GEMGateway to Educational Materials

Googlehttp://www.Google.com

GoogleDesktop http://desktop.google.com/

GoogleSimilar Pages http://www.googleguide.com/similar_pages.html

HFI,Human Factors International http://www.humanfactors.com/

HREOC,Human Resources Equal Opportunity Commission of the Australian FederalGovernment http://www.hreoc.gov.au/

HTML4.01, HyperText Markup Language. Raggett, D., Le Hors, & A., Jacobs, I.,(Eds), (1999). HTML 4.01 Specification http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/

HTTP,Hypertext Transfer Protocol -- HTTP/1.1. R. Fielding, R., Gettys, J., Mogul,J., Frystyk, H., Masinter, L., Leach, P., & Berners-Lee, T., (Eds), (1999).http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc2616

Hyperlecture

IEEE14.84.12.1 - 2002 Standard for Learning Object Metadata:

IEEE/LOM,IEEE Learning Technology Standards Committee .

IMSAccessibility http://www.imsglobal.org/accessibility/

IMSAccLIP, IMS Learner Information Package Accessibility for LIP

IMSAccMD, IMS AccessForAll Meta-data Specification

IMSAG, IMS Accessibility Guidelines for Education

IMSGLC, IMS Global Learning Consortium http://www.imsglobal.org/

INCITSV2 community http://v2.incits.org/

InclusionUK http://inclusion.uwe.ac.uk/

InternationalAcademy of Digital Arts and Sciences http://www.iadas.net/

ISOcoordinate ref system see http://www.isotc211.org/

ISO2788 standard (

ISO/IECJTC1 SC36 http://jtc1sc36.org/

ISO/IECJTC1 SC35 WG8 User Interfaces for Remote Interaction

LMSAngel http://www.angellearning.com/

MMI-DC,European Committee for Standardization Meta-Data (Dublin Core) Workshop

Macromediaoriginally http://www.macromedia.com/software/now Adobe and at http://www.adobe.com/products/

MathML,Mathematics Markup Language http://www.w3.org/Math/

METS,Metadata Encoding and Transmission Standard,

MRCUNC, Metadata Research Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

MRPUCB, Metadata Research Program (formerly OASIS), University of California,Berkeley http://metadata.sims.berkeley.edu/index.html

NCD,US National Council on Disability http://www.ncd.gov/

NLS,National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, Library ofCongress http://lcweb.loc.gov/nls/

NIST,National Institute of Standards and Technology http://www.nist.gov/

OAI,Open Archives Initiative http://www.openarchives.org/

OCLC,Online Computer Library Center http://www.oclc.org

Ontopiahttp://www.ontopia.net/omnigator/models/index.jsp

OpenUniversity, UK, http://www.open.ac.uk/

OZeWAI2004 Conference http://www.OZeWAI.org/2004/

OZeWAI2004 Conference http://www.OZeWAI.org/2007/

PDF,Portable Document Format

PNP,ISO standard text of FCD 24751-2, Individualized Adaptability and Accessibilityin E-learning,

Education and Training Part 2: Access For All Personal Needs and PreferencesStatement http://jtc1sc36.org/doc/36N1140.pdf

POWDER,http://www.w3.org/2007/powder/

RDF,Resource Description Framework. http://www.w3.org/RDF/

RNIB,Royal national Institute for the Blind. http://www.rnib.org.uk/

RSS,Really Simple Syndication or RDF Site Summary,

s.508Rehab Act .....

SAKAI,SAKAI Collaboration and Learning Environment for Education

SALT,Specifications for Accessible Learning Technologies

SC36,ISO JTC1 SC36, Learning, Education and Training standards

SGMLStandard Generalized Markup Language ISO 8879

SMILSynchronised Multimedia Integration Language

STEVEMuseum http://www.steve.museum/

STSNSpeech-to-Text Services Network http://www.stsn.org/

SVG,World Wide Web Consortium's Scalar Vector Graphics

SVGCapability

SWAP,Smart Web Accessibility Platform http://www.ubaccess.com/swap.html

SWG-A,ISO/IEC JTC1 SWG-A http://www.jtc1access.org/

TBPTalboks-och Punktskrift Biblioteket, Sweden http://www.tpb.se/

testlabis a european http://www.svb.nl/project/testlab/testlab.htm

TextHelpSystems Inc. http://www.texthelp.com/

TheLibrary of Congress National Library Service for the Blind and PhysicallyHandicapped (NLS). The Union Catalogue (BPHP) and the file of In-ProcessPublications (BPHI) can both be searched via the NLS website (see

TILE,The Inclusive Learning Exchange http://www.barrierfree.ca/tile/

TopicMaps http://www.topicmaps.org/

TRACEhttp://www.trace.wisc.edu

UAAG,World Wide Web Consortium WAI's User Agent Accessibility Guidelines

ubAccesshttp://www.ubaccess.com/

UML,Unified Modeling Language http://www.uml.org/

UNEnable http://www.un.org/disabilities/

Universityof Toronto, http://www.utoronto.ca/

URI,Universal Resource Identifier http://labs.apache.org/webarch/uri/

VISUCAThttp://www.cnib.ca/library/visunet/

W3C,World Wide Web Consortium, http://www.w3c.org/

WAI,World Wide Web Consortium's Web Accessibility Initiative

WAI-AGEhttp://www.w3.org/WAI/WAI-AGE/

WGAC,Chisholm, W., Vanderheiden, G. and Jacobs, I. (1999). Web Content AccessibilityGuidelines Version 1.0 http://www.w3.org/TR/WAI-WEBCONTENT/

WCAG-2Web Content Accessibility Guidelines Version 2.0 Caldwell, B., Chisholm, W.,Vanderheiden, G. and White, J. (2004). http://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/

WCAGWG http://www.w3.org/WAI/GL/

Web-4-Allhttp://web4all.ca/

WGBH/NCAM,The Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family National Center for Accessible Media

Webbyaward winners http://www.webbyawards.com/

WG7,Working Group 7 of ISO JTC1 SC36, Learning, Education and Training

WSG,Web Standards Group http://webstandardsgroup.org/

WSISWorld Summit on the Information Society http://www.itu.int/wsis/

XML,World Wide Web Consortium's Extensible Markup Language (

Glossary of terms

accessibility

a successful matching of information and communications toa user's needs and preferences to enable the user to interact with and perceivethe intellectual content of the information or communications. This includesbeing able to use whatever assistive technologies or devices that arereasonably involved in the situation and that conform to suitably chosenstandards.

disabilities

people with ...

inclusive

doing what is reasonably required to ensure accessibilityfor the maximum number of people individually

'metadata' from ... 1.3 of AGLS Metadata revision ofusage guide....(check email from SA and Agnes)

“Metadata is just a new term for something that has beenaround for as long as humans have been writing. It is the Internet-age term forinformation that librarians traditionally have put into catalogues andarchivists into archival control systems. The term ‘meta’ comes from a Greekword that denotes ‘alongside, with, after, next’. More recent Latin and Englishusage would employ ‘meta’ to denote something transcendental, or beyond nature.Metadata, then, can be thought of as data about other data. Although there aremany varied uses for metadata, the term is commonly used to refer todescriptive information about online resources, generally called ‘resourcediscovery metadata’.

Resource discovery metadata is information in a structuredformat that describes a resource or a collection of resources. A metadatarecord, then, consists of a set of properties, or elements, which characteriseresources and which are used to describe a resource. For example, a metadatasystem common in libraries – the library catalogue – contains a setof metadata records with elements that describe a book or other library item:author, title, date of creation or publication, subject coverage, and the callnumber specifying location of the item on the shelf.”

resources

things that incl services and objects,

the Web

digital information and communication - includinginformation that points or provides pointers to non-digital information

United Nations Convention for People withDisabilities, Article 2 Definitions

“For the purposes of the present Convention:

"Communication" includes languages, display oftext, Braille, tactile communication, large print, accessible multimedia aswell as written, audio, plain-language, human-reader and augmentative andalternative modes, means and formats of communication, including accessibleinformation and communication technology;

"Language" includes spoken and signed languagesand other forms of non spoken languages;

"Discrimination on the basis of disability" meansany distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability which hasthe purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment orexercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamentalfreedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any otherfield. It includes all forms of discrimination, including denial of reasonableaccommodation;

"Reasonable accommodation" means necessary andappropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a disproportionate orundue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons withdisabilities the enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of allhuman rights and fundamental freedoms;

"Universal design" means the design of products,environments, programmes and services to be usable by all people, to thegreatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specializeddesign. "Universal design" shall not exclude assistive devices forparticular groups of persons with disabilities where this is needed.” (

RelevantAccessibility Organisations

While there are many organisations related to accessibility,too many to even name, there are some organisations that have played asignificant role in shaping the Web since its inception. Some of these will beidentified here as they usually also provide many online resources and anyunderstanding of the 'literature' of accessibility of the Web or metadatarelating to it necessarily relies on familiarity with the work of theseorganisations.

WAI

W3C's approach has evolved over time but it is currentlyunderstood as promoting 'universal design'. This idea was fundamentalto WCAG 1.0 and is maintained for the forthcoming (WCAG 2.0) guidelines for thecreation of content for the Web. WCAG is complemented by guidelines forauthoring tools that reinforce the principles in the content guidelines and W3Calso offers guidelines for browser developers. Significantly, the guidelinesare also implemented by W3C in its own work via the Protocols and FormatsWorking Group who monitor all W3C developments from an accessibilityperspective.

W3C entered the accessibility field at the instigation ofits director and especially the W3C lead for Society and Technology at thetime, Professor James Miller, shortly after the Web started to take asignificant place in the information world. W3C established a new activityknown as the Web Accessibility Initiative with funding from internationalsources. From the beginning, although W3C is essentially a members' consortium,in the case of the WAI, all activities are undertaken openly (all mailing listsetc are open to the public all the time) and experts depend upon input frommany sources for their work.

The W3C/WAI activity has done more than develop standardsover the years through its fairly aggressive outreach program. It publishes arange of materials that aim to help those concerned with accessibility to workon accessibility in their context.

TRACE

The TraceResearch & Development Center is a part of the College of Engineering,University of Wisconsin-Madison. Founded in 1971, Trace has been a pioneer inthe field of technology and disability.

Trace CenterMission Statement:

To preventthe barriers and capitalize on the opportunities presented by current andemerging information and telecommunication technologies, in order to create aworld that is as accessible and usable as possible for as many people aspossible. ...

Tracedeveloped the first set of accessibility guidelines for Web content, as well asthe Unified Web Access Guidelines, which became the basis for the World WideWeb Consortium's Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 [

Wendy Chisholm, who originally worked at TRACE was aleading staff member of WAI for many years and author of a number of theaccessibility guidelines and other documents.

ATRC

The Adaptive Technology Resource Centre is at theUniversity of Toronto. It advances information technology that is accessible toall through research, development, education, proactive design consultation anddirect service. The Director of ATRC, Professor Jutta Treviranus, has beensignificant in the standards work in many fora and the group has contributedthe main work on the ATAG. They are also largely responsible for initiating thework for the AccessForAll approach to accessibility and the technicaldevelopment associated with it.

WGBH/NCAM

The Carl and Ruth Shapiro Family National Center for AccessibleMedia is part of the WGBH, one of the bigger public broadcast media companiesin the USA. Henry Becton, Jr., President of WGBH, is quoted on the WGBH Website as saying that:

WGBHproductions are seen and heard across the United States and Canada. In fact, weproduce more of the PBS prime-time and Web lineup than any other station. Homevideo and podcasts, teaching tools for schools and home-schooling, services forpeople with hearing or vision impairments ... we're always looking for new waysto serve you! (WGBH About,2007)

With respect to people with disabilities, the site offersthe following:

People whoare deaf, hard-of-hearing, blind, or visually impaired like to watch televisionas much as anyone else. It just wasn't all that useful for them ... until WGBHinvented TV captioning and video descriptions.

Public television was first to open these doors. WGBH is working to bring mediaaccess to all of television, as well as to the Web, movie theaters, and more (

NCAM is a major vehicle for these activities within themedia context and its Research Director, Madeleine Rothberg, has been asignificant researcher and author in the work that supports AccessForAll in arange of such contexts.

Relevant Accessibility StandardsOrganisations

In addition to organisations that have been involved in theresearch and development that have led to the AccessForAll approach and standards,there have been the standards bodies themselves that have not only publishedstandards but also initiated work that has made the standards' developmentpossible. In many cases, standards are determined by 'standards' bodies thatare, as in the case of the International Organisation for Standardization [

W3C's role in the standards world is often described as differentfrom, say, the role of ISO because of the structure of the organisation andalso the processes used to develop specifications for recommendation (de factostandards). W3C membership is open to any organisation and tiered so thatlarger more financial organisations contribute a lot more funding than smalleror not-for-profit ones. The work processes are defined by the W3C so thatworking groups are open and consult widely and prepare documents which arevoted on by members and then recommended, or otherwise, by the Director of theW3C, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. They are published as recommendations but usuallyreferred to as standards and certainly, in the case of the accessibilityguidelines, are de facto standards. In many countries, including Australia,they have been adopted into local laws in one way or another.

ISO

ISO collaborates with its partners, the InternationalElectrotechnical Commission [IEC] and theInternational Telecommunication Union [ITU-T],particularly in the field of information and communication technologyinternational standardization.

ISO makes clear on their Web site, that it is

a globalnetwork that identifies what International Standards are required by business,government and society, develops them in partnership with the sectors that willput them to use, adopts them by transparent procedures based on national inputand delivers them to be implemented worldwide (

ISO federates 157 national standards bodies from around theworld. ISO members appoint national delegations to standards committees. In all,there are some 50,000 experts contributing annually to the work of theOrganization. When ISO International Standards are published, they areavailable to be adopted as national standards by ISO members and translatedinto a range of languages.

The Joint Technical Committee 1 of ISO/IEC is forstandardization in the field of information technology. At the beginning ofApril 2007, it had 2068 published ISO standards related to the TechnicalCommittee and its Sub-Committees; 2068; 538 published ISO standards under itsdirect responsibility; 31 participating countries; 44 observer countries; atleast 14 other ISO and IEC committees and at least 22 internationalorganizations in liaison (

JTC1 SC36 WG7 is the working group for Culture, Languageand Human-functioning Activities within the Sub-Committee 36 for IT forLearning Education and Training. It is this working group that has developedthe AccessForAll standards for ISO. Co-editors for these standards come fromAustralia (Liddy Nevile), Canada (Jutta Treviranus) and the United Kingdom(Andy Heath), but there have been major contributions from others in the form ofreviews, suggestions, and discussion and support.

IMS

The IMS Global Learning Consortium [

A joint project between WGBH/NCAM and IMS initiated thework on AccessForAll with a Specifications for Accessible Learning Technologies(SALT) Grant in December 2000. Anastasia Cheetham, Andy Heath, JuttaTreviranus, Liddy Nevile, Madeleine Rothberg, Martyn Cooper and David Wienkaufwere particularly prominent in this work.

DCMI

The Web site describes the Dublin Core Metadata Initiativeas

an openorganization engaged in the development of interoperable online metadatastandards that support a broad range of purposes and business models. DCMI'sactivities include work on architecture and modeling, discussions andcollaborative work in DCMI Communities and DCMI Task Groups, annual conferencesand workshops, standards liaison, and educational efforts to promote widespreadacceptance of metadata standards and practices (DCMI,2007).

The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working formallyon Dublin Core metadata for accessibility purposes since 2001. While the earlywork focused on how metadata might be used to make explicit the characteristicsof resources as they related to the W3C WCAG, this goal has been realised inthe AccessForAll work. The DCMI Accessibility Community has been working inclose collaboration with the IMS and ISO efforts but it has engaged themetadata community, and therefore those working primarily in a wider contextthan education, especially including government and libraries. The author hasbeen chairperson of the DCMI Accessibility community since its inception.

CEN

The European Committee for Standardization, was founded in1961 by the national standards bodies in the European Economic Community andEuropean Free Trade Association countries. CEN is a forum for the developmentof voluntary technical standards to promote free trade, the safety of workersand consumers, interoperability of networks, environmental protection,exploitation of research and development programmes, and public procurement (

A number of CEN committees have been involved in thedevelopment of AccessForAll, either in the form of contributed funding as forthe MMI-DC, or in their independent review of the development of AccessForAlland how it will work in their context if it is adopted by the other standardsbodies. Significant in this work have been Martyn Cooper, Martin Ford, AndyHeath, and Liddy Nevile who have all worked on CEN projects in recent years.The context for this work has included but not been limited to education.

Cancore, CETIS,AGLS, etc

There are a number of other standards bodies or regionalassociations that have considered the work in depth and contributed in someway. In fact, in early 2007, IMS versions of the specifications had beendownloaded 28,082 times and the related guidelines more than 176,505 times.(Rothberg, 2007) CanCore has published the CanCore Guidelines for the"Access for All" Digital Resource Description Metadata Elements (

The Centre for Educational Technology and InteroperabilityStandards [CETIS] in the UK provides anational research and development service to UK Higher and Post-16 Educationsectors, funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee. CETIS has publishedsome summary documents about the

Chapter 1: Preamble

Introduction

The [UnitedNations] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and its OptionalProtocol were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 13 December2006, and opened for signature on 30 March 2007. On 30 March, 81 Member Statesand the European Community signed the Convention, the highest number ofsignatures of any human rights convention on its opening day. 44 Member Statessigned the Optional Protocol, and 1 Member State ratified the Convention. TheConvention was negotiated during eight sessions of an Ad Hoc Committee of theGeneral Assembly from 2002 to 2006, making it the fastest negotiated humanrights treaty. The Convention aims to ensure that persons with disabilitiesenjoy human rights on an equal basis with others [

By March 31, 2008, there were 126 signatories to the UnitedNations Convention, 71 signatories to the Optional Protocol, 18 ratificationsof the Convention and 11 ratifications of the Optional protocol. Australiasigned the Convention but has not ratified it (

The idea that inclusive treatment of people eliminates theneed for special considerations for people with disabilities is at the heart ofthe research reported in this thesis. It is derived from what has been definedas the social model of disability (

The social model of disability spreads responsibility forinclusion across the community. This research aims to enable continuous,distributed, community effort to make the World Wide Web inclusive.

For a decade, effort to make the Web accessible has focusedon following, or otherwise, a set of guidelines that have come to be treated asspecifications. These guidelines have been proven inadequate to ensureaccessibility for all, because the universal accessibility model on which theydepend is flawed. Recent estimates of the accessibility of the Web are as lowas 3% (

If a user is blind, eyes-busy or using a small screen,instructions about how to get from one place to another presented as a map maybe incapable of perception while a text version that can be read out and heardwould be perceptible. Providing a text description of travel routes is anexample of an accessibility improvement for a map. Managing the map and the newversion so that it is associated with the map, and discoverable at the sametime as the map, is what catalogue records or metadata can do for digitalobjects.

The research advocates a process to support ongoingincremental improvement of accessibility. This depends upon efficientmanagement and description of distributed resources and their improvements, anddescriptions of them, so they can be matched to people's individual needs andpreferences. The research elaborates what is called AccessForAll metadata (

The research distinguishes the context in which earlieraccessibility work took place. In what might be thought of as a ‘Web 1.0’environment, one-way publishing was the dominant activity. In the current ‘Web2.0’ environment, interactive publication happens across the Web inunpredictable ways, despite authors and publishers who provide well-structured,cohesive Web sites. Most people are learning to 'Google' and approachinformation from a range of perspectives and directions, often coming intoresources through what is effectively a back door, and taking from resourceswhat is of interest but disregarding or discarding the rest. The research alsorelies upon the interactivity and energy available from what is known as socialnetworking that is occurring within the Web 2.0 environment (

The research is not limited to classic 'Web pages', butincludes access to all resources, including services, that are digitallyaddressed. AccessForAll metadata already describes digital resources and isbeing extended to describe a wider range of objects including events and places(ISO/IEC JTCISC 36, 2008). Descriptions of the accessibility of those physical placesand events will be Web addressable, so the access to those places will be 'onthe Web'.

Background

The United Nations publishes a map (Figure 1) that showsinvolvement in the United Nations (UN) Convention for the Rights of People withDisabilities. As of June 2008, more than eighteen months after the Conventionwas adopted by the UN, Australia had only signed the convention but notratified it. Unless it is ratified by the Australian government, it has nolegal status in Australia. On the other hand, Australians have been involvedfor many years in international efforts with W3C,ISO, IMSGLC, CEN, and others to ensure thatinformation technology and digital resources are accessible to everyone. Theyhave actively participated in the work of the World Wide Web Consortium [

The recentUnited Nations convention on the rights of people with disabilities clearlystates that accessibility is a matter of human rights. In the 21st century, itwill be increasingly difficult to conceive of achieving rights of access toeducation, employment health care and equal opportunities without ensuringaccessible technology (

Making the Web accessible to everyone has proven moredifficult than anticipated. While Roe (

At theMuseums and the Web 2006 conference, one word had the power to abruptly silencea lively discussion among multimedia developers: accessibility. When the topicwas introduced during lunchtime conversation to a table of museum webdesigners, the initial silence was followed by a flurry of defensivecomplaints. Many pointed out that the lack of knowledgeable staff and fundingresources prevented their museum from addressing the “special” needs of theonline disabled community beyond alternative-text descriptions. Others fearedthat embracing accessibility in multimedia meant greater restrictions on theircreativity. A few brave designers admitted they do not pay attention to theguidelines for accessibility because the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines(WCAG) 1.0 standards are dense with incomprehensible technical specificationsthat do not apply to their media design efforts. Most importantly, only oneinstitution had an accessibility policy in place that mandated a minimum levelof access for online disabled visitors. Conversations with developers ofmultimedia for museums about accessibility were equally restrained. Developersfrequently blamed the authoring tools for the lack of support for accessiblemultimedia development. Other vendors simply dismissed the subject or admittedtheir lack of knowledge of the topic. Only one developer asked for advice onhow to improve the accessibility of their learning applications (

Roe (

About 15% ofEuropeans report difficulties performing daily life activities due to some formof disability. With the demographic change towards an ageing population, thisfigure will significantly increase in the coming years. Older people are oftenconfronted with multiple minor disabilities which can prevent them fromenjoying the benefits that technology offers. As a result, people withdisabilities are one of the largest groups at risk of exclusion within theInformation Society in Europe.

It isestimated that only 10% of persons over 65 years of age use internet comparedwith 65% of people aged between 16-24. This restricts their possibilities ofbuying cheaper products, booking trips on line or having access to relevantinformation, including social and health services. Furthermore, accessibilitybarriers in products and devices prevents older people and people withdisabilities from fully enjoying digital TV, using mobile phones and accessingremote services having a direct impact in the quality of their daily lives.

Moreover,the employment rate of people with disabilities is 20% lower than the averagepopulation. Accessible technologies can play a key role in improving thissituation, making the difference for individuals with disabilities betweenbeing unemployed and enjoying full employment between being a tax payer orrecipient of social benefits (

People with disabilities who are alienated byinaccessibility are regarded by Australian law (HREOC, 2002) as discriminatedagainst. They are able to claim damages from those who discriminate againstthem if all relevant conditions are satisfied. This means Australia recognizesa general right. It is, therefore, incumbent on a victim to prove, within thelegal system, that they have unreasonably suffered from discrimination.Although such a course has been used, reported cases are rare and, as withother cases likely to provoke negative publicity. Such cases would normally besettled out of court where possible, and so not publicly reported. Such a legalsituation does not operate as a major threat to large organisations, especiallyas so far the damages awarded so far have not been substantial, e.g. Maguire vSydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (

Accessibility efforts in many cases aim to make a singleresource universally accessible to everyone.Universal accessibility involves providing the same resource in many forms sothat people with disabilities can use the full range of perceptions to accessit across all platforms, fixed and mobile, standard and adaptive. Universalaccessibility is distinguished from individual accessibility or accessibilityto an individual user. Many resources are individually accessible while notuniversally accessible and many universally accessible resources (as defined bythe standards in use) are not accessible by some individual users (

Reinforcing the disinclination to worry about accessibilityis the common belief that it costs a lot to make resources universallyaccessible (Steenhout,2008). Frequently, it is left to a semi-technical person in a relativelyinsignificant position within an organisation or operation to championaccessibility as best they can. Anecdotally, they frequently report that allwas going well until the resource was about to be released. Then, the marketingmanager or some other more significant participant chose to add a particularfeature and not be constrained by accessibility concerns. (In the 1990's,Nevile was responsible for the accessibility of original design of two majorgovernment portals, the Victorian BetterHealth Channel and the Victorian

Economic factors are, therefore, important in the contextof accessibility. Many believe that accessibility means more expenses whenresources are being developed and more resources being supplied to the range ofusers of those resources. It is true that making an inaccessible resource accessiblecan take considerable effort, expertise and expense and, even then, is notalways possible. On the other hand, some publishers are finding that by makingaccessibility a priority, they actually gain financially through cost savings (

Practicality is important. It has long been known that itis not always possible to make an inaccessible resource accessible withouthaving to compromise some of the characteristics of the resource, depending onwhat sort of resource it is. If designers provide an attractive 'look and feel'for a Web site, for example, it may not be possible to have exactly that lookand satisfy all the accessibility specifications. Additionally, those who areexperts in accessibility are not usually designers but more often technicalpeople. In practice, a designer who works within the accessibility constraints isable to design creatively and avoid the accessibility pitfalls.

One common reason that resources are not accessible is thatthey are dependent on a software application that does not render the content,or does not control or display the content in ways that make it accessible toeveryone. Many people with disabilities use specialised equipment or softwareto gain access to content. Many people use mobile phones, and others usescreens with content projected on to them, or printers, or old computers. Sometimesthe content creator takes the end user into account. Unfortunately, this oftenmeans they arbitrarily anticipate, for example, that it will be printed onlocal-standard sized paper, in which case they fix the electronic version ofthe resource to match the way they expect it to appear on paper. This does notalways work for the paper version because the local standards differ. Neitherdoes it work for the digital version of the resource because rarely are screensizes or windows appropriate for this. In cases where users have unusual needsor preferences, such as a need to change the font size or reverse the coloursof the background and foreground. it is unlikely the necessary changes can bemade. It is possible, however, where the digital version of the fixed printversion is very well encoded for accessibility,. The World Wide Web Consortium[W3C] has developed a technology that allowsa single resource to be presented in a variety of ways, depending on the medium,and explicitly for the user to have one form of presentation that overrides anymade available by the publisher of the resource or the browser software [

Many think of the Web as 'homepages' or Web sites. This isnot sufficient. A Web page may contain links to documents that reside indatabases, open or closed, and those 'documents' might be simply someapplication-free content, or they might be complex combinations of multimediaobjects, even dynamically assembled for the individual user, locked intospecific applications. The Web Accessibility Initiative [

The WAI set of guidelines, originally three for authoringtools, users agents and content [WebContent Accessibility Guidelines, WCAG], have been in constant developmentor revision for more than a decade (Chapter 4).They have been adopted in many countries and used by developers all around theworld. Despite this incredible effort, the Web is far from accessible toeveryone (Chapters 3,

In recent years, total dependence on the WAI work and itsderivatives (such as s. 508 that wasadded to the US Disabilities Discrimination Act [

In 2008, more and more such services are emerging. What issignificant is not simply their number. It is that they represent a significantshift in thinking about accessibility. If resources are not going to be createduniversally accessible, or found in a universally accessible form, and it isunlikely there will be a significant change in this situation, it makes senseto think more about what can be done post-production.

Post-production techniques were a feature of the

Going a little further, the

An outdated view of accessibilityand the Web

The original use of the World Wide Web was to enable a fewpeople scattered around the world to work together on shared files located ontheir own computers, to make them discoverable using a Uniform/UniversalResource Identifier [URI],and to access them using the HyperText Transfer Protocol [

The research establishes that the dominant model ofaccessibility work is still grounded in the early Web, a network of staticdocuments that may be updated but are usually from a single source. In thisthesis, the term Web 1.0 is used to designate the Web as it was commonly usedin its first decade (1995-2005). O'Reilly (

Web 1.0 work assumes editorial control over publishing,even where the authors come from a single organisation and this task isundertaken by a number of people. In such cases, in fact, many organisationsimpose both style guides (or the equivalent) on the authors and/or providetemplates within which those authors have constrained scope for their content.In such circumstances, it might be possible to force adherence to certain stylestandards, as it was in the earlier days when documents to be printed wereencoded in Standard Generalized Markup Language [

A side-effect of Web 1.0 work is that many people still donot recognise that they can use standard Web pages and Web authoring tools, inalmost exactly the same way as they use non-standardised proprietary officetools, including to format, print, exchange and manage other documents. Manypeople are still using office tools that do not take advantage of theaccessibility possible with available technologies. Organisations in whichproprietary office tools are used form sub-cultures around those tools, andparticipants develop materials (resources) that suit the particular softwaretools. They are often not aware that their single resources could be as easilycreated and managed but far more flexible and interoperable not only betweensoftware systems, but also across ranges of modalities (on paper, on individualscreens, as presentations on large screens, read aloud, etc.). Proprietaryinterests and competition have encouraged proprietary developers to distinguishtheir software by adding features often regardless of the inaccessibilitysimultaneously introduced by those features (Nevile, personal observations).

At the time of writing, there is a worldwide debate on thewisdom of adopting the Microsoft specification Office Open XML as anInternational Standards Organisation [ISO]standard for documents. One reason is the problem of accessibility that mayflow from that decision (

The research establishes that the historic view ofaccessibility is no longer effective. The complexity of satisfying the originalguidelines is shown to be out of the range of most developers. There are toomany techniques involved; they are not explicit; they cannot always be testedwith certainty; they do not completely cover even chosen use cases and are notintended to cover all user requirements; they are contradictory in some cases;they have not been applied systematically, and anyway, they do not apply to allpotential information and communications. All of these claims are documented inthis thesis.

A new approach to accessibility foran updated Web

This thesis is not alone in making the claims above: thereare many authors and developers both writing and acting; some people havestarted work on post-production and even post-delivery reparation of resourceslacking in accessibility, and others are proposing new ways of thinking aboutaccessibility. Their work is considered in detail in the research.

What this thesis offers is an argument in favour of anon-going process approach to accessibility of resources that supportscontinuous improvement of any given resource, not necessarily by the author ofthe resource, and not necessarily by design or with knowledge of the originalresource, or by contributors who may be distributed globally. It argues thatthe current dependence on production guidelines and post-production evaluationof resources as either universally accessible or otherwise, does notadequately provide for either the accessibility necessary for individuals orthe continuous or evolutionary approach possible within what is defined as aWeb 2.0 environment. It argues that a distributed, social-networking view ofthe Web as interactive, combined with a social model of disability, given themanagement tools of machine-readable, interoperable AccessForAll metadata, asdeveloped, can support continuous improvement of the accessibility of the Webwith less effort on the part of individual developers and better results forindividual users.

As outlined above, there are a number of ways to makeresources accessible. Relying solely on authors to 'do the right thing' byfollowing the universal accessibility approach has generally failed to makeresources universally accessible (Chapter 4)but many resources are nevertheless suitable for individual users, if only theycan find them. Similarly, most resources that are universally accessible arenot discoverable as such.

In Europe, there have been moves to apply metadata toresources (to catalogue them) that declare their accessibility in terms ofconformance with various available specifications: the UK government hasmandated certain provisions (

Metadata that merely identifies resources that have beenmarked as accessible is not particularly reliable and anyway, as is shown below(Chapter 4), conformance with thebest-known guidelines does not necessarily mean a resource is universallyaccessible. Certainly, such metadata does not say if the resource is optimisedfor any particular individual user seeking it. More specific metadata isrequired if it is to be useful to the individual user. This has been recognisedby the authors of the WCAG guidelines and there is provision in the forthcomingversion of WCAG for metadata as a result of the AccessForAll work (

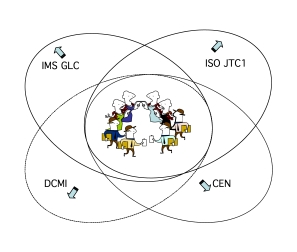

If resources are to be made more accessiblepost-production, they will need to be discoverable prior to being delivered andfound to be inaccessible and any missing or supplementary components, orservices to adapt them, will also need to be discovered. Resource descriptions,like catalogue records, can usefully contin descriptions of the accessibilitycharacteristics of resources without any need for declaring if the resource isor is not universally accessible. Such a description is known as AccessForAllmetadata and discussed in detail below (Chapter7). AccessForAll metadata has been adopted by four major standards bodies.First, the IMS Global Learning Consortium [IMSGLC] for the education sector. Then the Joint Technical Committee of theInternational Organisation for Standardization/International ElectrotechnicalCommission. Its, Sub-Committee 36, [ISO/IEC JTC1SC36], adopted it again for the education sector. The Dublin Core MetadataInitiative [DCMI] is adopting it forgeneral metadata, for all sectors, and most recently, Standards Australia hasadopted if for the AGLS Metadata Standard [AGLS],for all Australian resources.

This thesis describes the background, theories, design anddevelopment of the metadata, as documented in the various published orforthcoming standards, and work associated with its adoption by variousstakeholders.

In addition to metadata that describes the accessibilitycharacteristics of resources, it is necessary to define metadata to describethe accessibility needs and preferences of users. 'AccessForAll' metadata isbest used to match resources to users' needs and preferences, automaticallywhere possible. Determining how such a match might be achieved in a distributedenvironment is a continuing interest of the author and colleagues in Japan,especially in as much as it relates to the use of the Functional Requirementsfor Bibliographic Records [FRBR],OpenURI (

Usability is well established as a criterion for theutility of a resource (Nielsen, 2008). Aflexible approach including usability in a loose sort of 'tangram' model couldsignificantly improve the Web's accessibility (

Jakob Nielsen useit.com: Jakob Nielsen'sWebsite “Understanding and significance of accessibility”

Understanding accessibility is not easy given the hugenumber of different contexts and requirements possible. In addition, there aremany definitions.

For the purposes of the research, accessibility is definedas a successful matching of information and communications to an individualuser's needs and preferences to enable that user to interact with and perceivethe intellectual content of the information or communications. Thisincludes being able to use whatever assistive technologies or devices arereasonably involved in the situation and that conform to suitably chosenstandards. Explanations of the more detailed characteristics of accessibilityare considered in Chapter 3.

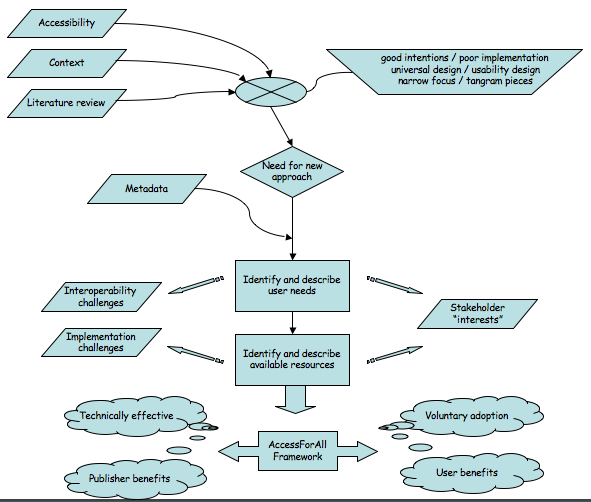

The literature reveals two significant things: a currentcommon approach to accessibility that is significantly reliant on universalaccessibility, as promoted by the World Wide Web Consortium [

Almost onein five Australians has a disability, and the proportion is growing. The fulland independent participation by people with disabilities in web-basedcommunication and information delivery makes good business and marketing sense,as well as being consistent with our society's obligations to removediscrimination and promote human rights. (

In 2005, estimates of accessibility were as low as 3% (

Microsoft Corporation commissioned research that suggeststhe benefits of accessibility will be enjoyed by 64% of all Web users (

Brian Kelly (

What wecan’t say is that the Web sites which fail the automated tests are necessarilyinaccessible to people with disabilities. And we also can’t say that the Websites which pass the automated tests are necessarily accessible to people withdisabilities.

The lack ofaccessibility solutions leads to the need for a new, comprehensive process foraccessibility that includes the use of metadata to facilitate discovery anddelivery of digital resources that are accessible to individuals according totheir particular needs and preferences at the time of delivery. When a user hasa constraint that renders information inaccessible to them, they are deemed tohave a need, such as when a highly mobile person using a telephone cannot use asmall scale map because it cannot be displayed on their tiny low-resolutionscreen or a blind person requires Braille. User preferences are less crucialresponses to constraints for the individual user. It should be noted that someusers have very specific needs that must be satisfied whereas other users maybe satisfied by any from a range of preferences.

AccessForAll philosophy

The more information is mapped and rendered discoverable,not only by subject but also by accessibility criteria, the more easily andfrequently inaccessible information for the individual user can be replaced oraugmented by information that is accessible to them. This, in turn, means lessdamage when an individual author or publisher of information fails to maketheir information accessible. This is important because, as is shown (see

Widespread-mapping of information depends upon theinteroperability of individual mappings or, in another dimension, the potentialfor combining distributed information maps in a single search source. Theancient technique of creating atlases from a collection of maps is exemplary inthis sense (

Atlases would not be useful if every map were developedaccording to different forms of representation; the standardisation ofrepresentations enables the accumulation of maps to form the universal atlas.In the same way, the widespread mapping of accessible resources on the Web isachieved by the use of a common form of representation so that searches can beperformed across collections of resources. Interoperability is typically saidto function at three levels: structure, syntax and semantics (Weibel, 1997).Nevile & Mason (2005) argue that it does not operate at all unless there isalso system-wide adoption (see Chapter 12).

The AccessForAll team (the AfA team) worked to exploit theuse of metadata in the discovery and construction of digital information in away that could increase Web accessibility on a worldwide scale. The outcome isa set of specifications (now forthcoming as standards) that can be used toenable the production of an atlas of accessible versions ofinformation so that individual users everywhere can find something that willserve their purposes in a way that is independent of their choice of device,location, language and representational form. There are several ways in whichthis work needs to be followed by other work: to enable a similar selection ofuser interface components (see FLUID)and perhaps certification of organisations and systems that provide the newservice, or at least those that enable it by providing useful metadata (see

The AfA work takes advantage of the growing number ofsituations for which metadata is the management tool for digital of objects andservices and of people's needs and preferences with respect to them, so thatresources that are suitable can be discovered by users where they are well-described.AfA philosophy includes, in addition, that resources should be able to bedecomposed and re-formed using metadata to make them accessible to users withvarying devices, locations, languages and representation needs and preferences.Chapter 11 expands on some significant ifnot widespread adoption of this method. AfA metadata can be used immediately tomanage resources within a shared, closed environment such as the original oneestablished at the University of Toronto where the AccessForAll approachoriginated. There is, however, greater potential for it such as to use it in adistributed environment. Exactly how to do this is proving a challenge but theproblem is closely aligned to the problems being considered by W3C's workinggroup developing POWDER (W3C POWDER,2008) and hopefully will soon be overcome.

A metadata approach

In the case of the AccessForAll projects, Nevile has workedon many AccessForAll and other accessibility projects as the metadataresearcher.

BC wants a diagram of input etc here????

In the research, the basic computer science task ofclassification in first normal form (

Metadata research is looking for a means of fixingsemantics within a framework of vocabularies that are not aligned, usingtechnology that is evolving, and looking for appropriate means for declaringthe semantics in interoperable ways. Such research is being performed in a numberof leading universities around the world (MetadataResearch Center, University of North Carolina (MRC UNC);

At the Metadata Research Center, School of Information andLibrary Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a number ofprojects for developing metadata for specific domains have been funded andundertaken as research [MRC UNC]. Atypical example is provided by the KEE-MP project:

The goal ofthe Knowledge Exploration Environment for Motion Pictures (KEE-MP) project isto design and develop a prototype web system that will enable aggregation,integration, and exploration of diverse forms of discourse for film.

The mainresearch components of the project are:

Š

Š

Š

Such research does not depend upon standard researchtechniques (see Chapter 2), but nor is itdevelopment in the usual sense. While the direct output may be a prototypeproduct, the research is about metadata. Some of what is learned is inevitablywhat is not supported by metadata as it is used, and how effective the evolvingprinciples are, and what could improve them. It also touches upon theeffectiveness of the evolving principles of technical accessibility developmentand ways to improve it. The work of these projects is demanding and necessarilyinvolves a number of people.

AccessForAll metadata research and development

Metadata research projects, as shown above, often involve amulti-disciplinary team including both developers and researchers. In as muchas the research requires the use of new technologies, and they need to be builtand tested, developers are often essential to the work. In addition, there isusually a need for subject experts, who can contribute not just bareinformation but by advising on the structure of the knowledge of the domain,and how it is used. Finally, it is usually important to have someone who isable to cross-the disciplines, to understand how they interact in thecircumstances.

The Assistive Technology Resource Center [ATRC] at theUniversity of Toronto has a proud record of research and development. In thefield of accessibility, they have significant achievements and, specifically,were leaders in the use of database technologies to adapt resources to users’individual needs, with their product ‘The Inclusive Learning Exchange’ [TILE].

While there is a close connection between databasemanagement of resources and metadata, they are not the same. Databasedevelopers and researchers work on such aspects as the speed with which thedata can be manipulated by an application, the amount of data, etc. Metadataspecialists are customers for this work; their concern is more the semanticvalue of descriptions of the resources so that people, as well as machines, canuse the descriptions. Database specialists think in terms of the needs of thecomputational systems, metadata experts think about the substance of theresources and the discipline and thus its ontological principles. Metadataspecialists do not specialise in the discipline so much as in how to manage itsresources, and often learn this by working in a number of different contexts,and thus abstracting metadata principles that they can bring to bear in newsituations. It is this final activity that forms the research being reported.

TILE is a database application in which certain ‘fields’ orwhat programmers think of as tokens, prompt certain responses from acomputational system. Metadata is the result of an abstraction of such aprocess. Metadata is to do with the underlying model for such databases –how should the database be constructed to group resources, what triggers shouldit respond to, what inputs does it need, and so on. In this context, it can behelpful to think of the abstract work as developing a metadata schema such asthe abstract model for AccessForAll metadata (Chapter7).

In the AccessForAll interdisciplinary metadata team, there havebeen seven major players: Jutta Treviranus, Anastasia Cheetham and DavidWeinberg, in particular, from the Assistive Technology Resource Center [ATRC]at the University of Toronto, Canada (Universityof Toronto, Canada); Madeleine Rothberg from WGBH National Center forAccessible Media in Boston, USA (WGBH/NCAM);Liddy Nevile from La Trobe University, Australia; and Andy Heath from theUniversity of Sheffield (now at the Open University) and Martyn Cooper from theOpen University, United Kingdom (OpenUniversity, UK).

All in the team have been involved in accessibility workfor a number of years but from different perspectives. Nevile is clearly the metadataresearcher in the team, while Cheetham and Weinberg are responsible for thedevelopment of the prototype TILE, Heath is an expert in programming, andRothberg, Treviranus and Cooper are responsible for major accessibilityprojects in education. Treviranus is the outstanding accessibility expert.Treviranus is the Director of the ATRC and a leader in the field of disabilitywork involving technology, Director of the ATRC and its numerous projects, andChair of the W3C Authoring Tools Accessibility Guidelines Working Group [

The AccessForAll work has been undertaken in a number ofcontexts (as explained below) but always with the core team leading theefforts. The group emerged from the work being undertaken by the IMS GlobalLearning Consortium [IMS GLC] when theyadopted the ATRC model, and has moved to other contexts, as explained below.Nevile, the Chair of the DCMI Accessibility Working Group (now theAccessibility Community), is responsible for AccessForAll finding its way intothe DCMI world of metadata and has been responsible for developing theAccessibility Application Profile (or Module) for DCMI and all the schema anddocumentation required for an international technical standard (

Nevile is the primary DC 'metadata' person in theAccessForAll team (Appendix 1 and

AccessForAll metadata research

This thesis argues that metadata is an enabling technology thatshould be central and integral to anyin as much as it provideswhat is the role couldplay inin increasing accessibility.

Research objectives

This research establishes that careful metadata work isessential if metadata is to provide the infrastructure for AccessForAllpractices that can make the Web more accessible. With respect to metadata, theresearch challenges the structure, the syntax and the semantics of theAccessForAll work. It includes:

Š

Š

Š

Š